When Is Saying ‘No to Anti-Competitive Mergers’ Actually Anti-Competitive?

On February 15, 2023, Senator Elizabeth Warren spoke out against what she labels “anticompetitive bank mergers” as part of a larger speech lamenting 40 years of what she sees as lax antitrust enforcement resulting in competition in one market after another being placed on “life support” or being “snuffed out entirely.”

In that speech she also calls for bank regulators, including the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, which oversee national banks and federal thrifts, to stop approving “anti-competitive” mergers and join the Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission in doing the “heavy lifting” in the fight against monopolies. Her speech highlighted and promoted legislation she proposed in 2022 that would ban all mergers worth more than $5 billion.

The question is “does such a ban do more to stifle competition than promote it?” To answer that, this article looks at the state of competition within and outside the banking system from a national perspective and the likely effect that such a ban on bank mergers would have on competition.

Competition Within the Banking System Is Healthy

At the end of 2022, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insured more than 4,700 FDIC-banks and savings associations, and upwards of 72,000 branches were operating in the United States. While the number of branches per hundred thousand people has declined from a high of 35.9 in 2008 to 28.3 in 2021, that decrease has occurred as mobile and online banking have taken off and the population density of large metropolitan areas with numerous branches has increased. In fact, the number of branches an urban consumer has access to has increased slightly from 2.1 to 2.2 branches per 10,000 people from 2020, and the average distance to the nearest branch in urban areas has been stable at 1.5 miles. The average distance a rural consumer lives from a bank branch has declined to approximately four miles since 2020.

These changes on balance have increased the accessibility of banking services to reduce the number of unbanked and underbanked to people in the country to record lows, according to the FDIC’s most recent survey of unbanked and underbanked households. Accessibility provides choice and choice fuels competition.

Industry experts also have observed the effect of competition on the costs associated with banking with checking account maintenance fees, for instance, declining over the last year and rising less than 1 percent per year over the past five years. As the cost of consumer credit has increased over the last year with rising interest rates, banks have been competing more for bigger shares of household deposits by increasing rates paid on savings accounts and other deposits increasing. In 2009, savings rates averaged 0.21 percent APY but fell to 0.17 percent in 2010 and 0.11 percent in 2011. But today, however, consumers can find savings account and certificate of deposit rates at banks and credit unions approaching 7 percent.

The large number of U.S. banks, the wide availability of service from commercial banks, and evidence of price and feature competition demonstrate the choice consumers have and the high degree of retail competition among commercial banks in this country.

Another sign that competition among banks is healthy is the interest in creating new banks. Since the 10-year draught on new bank charters ended in 2017, the industry has seen an increase in applications and approvals for new banks, but that level has not yet approached the levels seen prior to 2008. A discussion elsewhere of the how policy, regulatory, and rhetorical actions have adversely depressed the number of new bank applications and approvals is long overdue.

In addition to the competition observed among commercial banks, banks also face stiff competition from nonbank competitors.

Competition From Outside the Banking System Is Robust

Over the last decade, much of the business that was exclusively conducted primarily by commercial banks in the past has moved outside the highly regulated system of state and federal banks and is now conducted by financial technology (fintech) companies and nonbank service providers.

In 2013, fintech companies accounted for just 5 percent of the personal loan market in the United States and by 2018 held 38 percent of the market, while banks’ share decreased from 40 percent to 28 percent. Deposits are moving to online providers too. “Megabanks used to control 35 percent of Gen Zers primary checking accounts. That has dropped to 25 percent since the pandemic,” according to industry analysts. Some analysts suggest that up to 28 percent of banking and payment services will be at risk of disruption because of competition from new business models brought about by fintech.

Investors seem to agree that challenger banks have the edge, and that can be seen in their valuation and performance over the last decade. Then, Acting Comptroller of the Currency Brian Brooks highlighted just how much better new technology companies focused on individual aspects of the financial service industry have performed compared with supermarket-style traditional banks, pointing out that the returns on indices of banks of all sizes—community, midsize and large banks—have been negative at one and three years and virtually flat at five years ending in 2020. Meanwhile, the returns on companies focused on individual aspects of banking—payments, payroll, capital markets and core technologies, information services—have been up by 50, 80 and up to 160 percent at three and five years.

That raises several policy questions involving the accumulation of systemic risk and consumer protection concerns with this high level of bank-like activity occurring outside the regulatory perimeter. Still, there are no signs that competition from outside the banking system for consumer and business customers will slow as long as the regulatory costs of nonbanks remains lower and innovation within traditional banking discouraged.

In light of the competition among banks and from outside competitors, what is a bank to do?

Banning Mergers Stops Smaller Banks from Competing with Larger Ones

Admittedly, running a successful banking business has never been more challenging and organic growth more difficult. Competition is intense. Regulatory cost and burden are high. And the economic environment is weak and uncertain.

At the same time, the stage for banking has changed in the last 30 years. While local communities and customers still represent a significant focus for bankers, the business of banking occurs on national and international scale.

As yield becomes a greater challenge and competition for revenue heats up, bankers and boards should look more at margin and efficiency. In its latest report on banking, McKinsey points out financial institutions with higher valuations tend to have a 40 to 60 percent lower cost to serve than the average universal bank and four times greater revenue growth. For banks facing challenges in this late stage of the economic cycle, the sense of urgency is high given their weak earnings. Banks face strategic risk and many will need to rethink their business models, and they will need to gain scale quickly to survive. Because of market segmentation and the number of bank competitors, scale is often best achieved through mergers and acquisitions, and McKinsey further points out the market is a target rich environment:

About 70 percent of market capitalization is held by banks that have a [price to book ratio] of higher than 1 (which is about half of all banks)—even though they account for only 30 percent of assets. Only 10 percent of these banks are already at scale, and they represent a market share of at least 10 percent; the rest of these “value-creating” banks could benefit from M&A to increase their scale.

There are two kinds of mergers that make the most business sense. First are mergers of banking organizations with completely overlapping franchises where more than 20 to 30 percent of combined costs can be taken out, and second are those where the banks combine complementary assets. When you take away the ability to make successful combinations out of business necessity, you introduce greater risk of bank failures and artificially increase the cost of banking by sustaining market inefficiencies and that is bad for business, bad for consumers, and anticompetitive. It also adds systemic risk.

Banning or a “soft” ban on mergers by slow-rolling approvals and rhetorically discouraging them also eliminates one of the market and regulatory tools that can be used to weed out weaker institutions by combining them with more safe and sound, better-run banks. Consider the $209 billion failure of Silicon Valley Bank and the $110.4 billion failure of Signature Bank in mid-March 2003. Both banks were considered heathy by regulators and the market just days before their failure and a merger or acquisition turned out to be a necessary part of their resolution. Purchases of the institutions or its assets after failure comes at a tremendous discount to the buyer but a horrible loss for shareholders and investors. It is entirely possible that an open-bank solution could have been achieved that would have protected all depositors, preserved value, and avoided government intervention had the prevailing attitude toward mergers been different. While the Department of the Treasury and federal bank regulators acted quickly to protect uninsured depositors as well as the depositors with federal deposit insurance and created a means for banks to tap necessary liquidity to help weather the storm, the drama and turbulence may have been prevented. While it will be sometime before the success of these measures can be fully evaluated, the second-guessing about the banks’ management and oversight and the corrective actions taken by regulators is well underway.

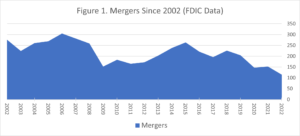

The recent outcry by some over mergers among banks could also lead people to believe that such activity is at a new frenzied pace or even on the rise, but that is not the case. FDIC data show that the number of mergers among commercial banks in 2022 was the lowest in the last 20 years.

Further, if the primary concern is with the market share and market-shaping power of the handful of megabanks over a trillion dollars in consolidated assets, the answer is not to prohibit any merger of hundreds of smaller banks that would exceed $5 billion in value. Rather regulators and policymakers should be encouraging such mergers and other business combinations where they make good business sense and allowing new competitors and innovators to enter the regulated banking space more easily to promote consumer choice and increase the number of banking organizations capable of operating and succeeding on a national and global scale and satisfying evolving consumer and market demands.

Such a ban on mergers would act as a moat protecting large incumbent players from competition much the way JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon described the Dodd-Frank Act ten years ago. Make no mistake, banning mergers and acquisitions is anti-competitive and does nothing to help bankers or consumers.

Put Patomak’s Banking Expertise to Work

Bank mergers and acquisitions are complicated, and the risks are pervasive. When bank management and boards consider business combinations of all sorts to increase the likelihood of succeeding in their long-term business strategies, it is critical to have advice and insight from people with decades of experience of navigating those processes. Patomak’s expertise can help banks navigate these challenges and meet their business goals. Contact us to learn how Patomak can help you navigate these challenges and help you meet your business goals.