Understanding CFPB Funding and Expenditures, FY 2010 – 2022

Understanding CFPB Funding and Expenditures, FY 2010 – 2022

I. Introduction

On October 3, 2023, the Supreme Court of the United States will hear oral argument in Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, et al., Petitioners v. Community Financial Services Association of America, Limited, et al., a case evaluating whether the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals erred in holding that the statute providing funding to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), 12 U.S.C. 5497, violates the Appropriations Clause, U.S. Const. Art. I, § 9, Cl. 7, and in vacating a regulation (the 2017 Payday Rule) promulgated at a time when the CFPB was receiving such funding. The Court is expected to announce its decision in this case by no later than June 30, 2024. Many observers are eager to read the Court’s opinion to understand what effect, if any, the disposition of the case will have on the actions of the CFPB and whether Congress will need to legislate to remedy any possible constitutional infirmities. However, because the CFPB is not subject to the regular appropriations process that applies to most federal Departments and agencies, few understand precisely how the CFPB obtains and expends its funding or the effect of its funding mechanism on federal budgeting and legislation. The purpose of this primer is to explain these processes and effects. The descriptions and figures used in this primer derive from various CFPB records released during the past thirteen years, unless otherwise noted. Most data sets end with Fiscal Year 2022 (FY 22) because, in a departure from historic practice, the CFPB has not yet publicly posted quarterly financial updates for the first three quarters of FY 23.

II. CFPB Funding

Section 1017 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (codified at 12 U.S.C. 5497) establishes how the CFPB obtains funding. The CFPB’s primary funding source is transfers from the Fed Board of Governors, a portion of the combined earnings of the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve Act requires the Reserve Banks to remit excess earnings to the U.S. Treasury after providing for operating costs, payments of dividends, and any amount necessary to maintain surplus. Accordingly, net earnings diverted to the CFPB are funds not available for remittance to the U.S. Treasury. Additionally, according to the Fed Board of Governors, since approximately September 2022, the earnings of the Reserve Banks have not been sufficient to cover their costs, so the Board of Governors has suspended remittances to the Treasury and is instead recording a deferred asset on the Fed’s balance sheet, which represents the amount of net earnings the Reserve Banks will need to realize in the future before the remittances to the U.S. Treasury may resume. Consequently, transfers to the CFPB, which the Board of Governors has not suspended despite its net quarterly losses, presently result in an equivalent increase in the combined amount of the deferred asset recorded by the Fed.

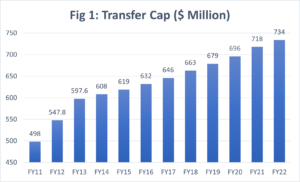

The CFPB operates on a fiscal year beginning on October 1 and ending on September 30. The maximum amount of funds that may be transferred from the Fed to the CFPB in any given fiscal year is set by a statutory formula that is indexed for inflation. See Figure 1 for a depiction of the annual fiscal year transfer caps.

To effectuate these transfers, the Director of the CFPB sends a quarterly letter to the Fed Board of Governors stating the amount the Director deems to be “reasonably necessary” to carry out the agency’s authorities. By law, the CFPB’s funding requests are not reviewable by the Fed, and funds derived from the Fed are not reviewable by Congress. Additionally, the CFPB’s budget and financial plans need not be approved by the White House Office of Management and Budget. Once the Board of Governors receives a transfer request letter, it transfers the funds into the “Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection Fund” (Bureau Fund), which is maintained at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY). By law, amounts deposited into the Bureau Fund may not be construed as “Government funds” or “appropriated monies” and are not subject to apportionment.

The total amounts that the CFPB has requested and received from the Fed Board of Governors in prior fiscal years appear in Figure 2.

In addition to Fed transfers, the CFPB has two additional (albeit minor) sources of funds. First, under the Interstate Land Sales Full Disclosure Act (ILSA), land developers are required to register subdivisions of 100 or more nonexempt lots and pay a fee when they register such subdivisions. The Dodd-Frank Act transferred responsibility for administering the ILSA program from HUD to the CFPB. The CFPB collects the ILSA fees, which it may retain and expend to cover its program operating costs. Second, the CFPB may invest the portion of funds held in the Bureau Fund that are not needed to meet current needs in Treasury securities. The CFPB typically invests in 3-month Treasury bills obtained in the open market and holds them to maturity. Interest earnings from the CFPB’s investments are deposited into the Bureau Fund.

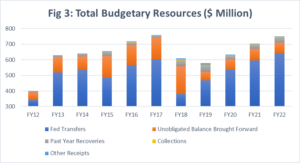

An important feature of CFPB funding is that (unlike with appropriations) the CFPB’s authority to expend available funds does not expire at the end of a fiscal year. Accordingly, the CFPB may retain the funds it does not expend each year and carry those forward from one fiscal year into the next, which increases the CFPB’s total available budgetary resources. For example, in FY 22, the CFPB obtained $641.5 million from the Fed, but also carried forward an unobligated balance in the Bureau Fund of $67.7 million from FY 2021, meaning that its total budgetary resources for FY 22 exceeded $750 million, an amount higher than the statutory transfer cap for that year. Between FY 12 and FY 22, the total budgetary resources of the CFPB grew at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 6.5%. For comparison, according to Federal Trade Commission (FTC) data, over the same period the CAGR in total new budget authority for the FTC (which is subject to Congressional appropriations) was 1.9%.

Total budgetary resources for the Bureau Fund appear in Figure 3.

Pursuant to the Dodd-Frank Act, the CFPB is also authorized to obtain civil monetary penalties from covered persons or service providers for violations of Federal consumer financial laws. Civil penalties obtained by the CFPB are deposited into the Consumer Financial Civil Penalty Fund, which is separate from the Bureau Fund. A detailed discussion of the Civil Penalty Fund is beyond the scope of this primer. However, while the CFPB generally obligates funds deposited in the Civil Penalty Fund for distribution to identified victim classes, to the extent that such victims cannot be located or payments are not practicable, the CFPB may use the funds on consumer education and financial literacy programs. Thus, the funds could theoretically be used as an alternative source of funding to offset some of the CFPB’s traditional programmatic expenses, which would effectively expand the CFPB’s budget authority. Notably, the CFPB has estimated that the unobligated balance of the Civil Penalty Fund as of September 30, 2023, will exceed $2.2 billion.

III. CFPB Expenditures

To expend funds, the CFPB maintains an account balance with the U.S. Treasury within the Treasury General Account. The CFPB requests cash disbursement from the Bureau Fund at the FRBNY to the CFPB’s Fund Balance with Treasury based on projections of future cash outlays. Funds held by the Treasury for the CFPB are available to pay agency liabilities and to finance authorized purchase obligations. Treasury processes cash receipts, such as fees collected from the ILSA program, and makes disbursements on the CFPB’s behalf.

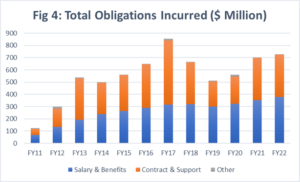

Each fiscal year, the CFPB incurs obligations for two principal object classifications: (1) employee compensation, and (2) contracts and support services. Each category is addressed in turn below. Total CFPB obligations incurred over time appear in Figure 4.

A.) Employee Compensation

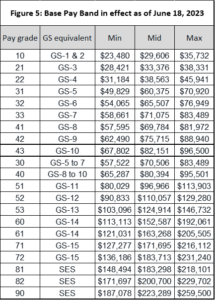

CFPB employees are not compensated according to the General Schedule (GS) classification and pay system applicable to most federal civil service employees. Under the Dodd-Frank Act (see 12 U.S.C. 5493(a)(2)), the Director is responsible for setting and adjusting the basic rates of pay for CFPB employees. However, the compensation (including benefits) provided to each class of employees must be “comparable” to the compensation then being provided by the Fed Board of Governors to its corresponding classes of employees. Accordingly, the CFPB has adopted a pay structure with multiple pay bands and a salary range within each band. Figure 5 depicts the base pay band structure in effect as of June 18, 2023.

Significant aspects of the CFPB’s compensation practices are subject to collective bargaining with the employee labor union (Chapter 335 of the National Treasury Employees Union). The most recent collective bargaining agreement (CBA) between the CFPB and the union was executed on September 12, 2017, just two months prior to former Director Cordray’s resignation. In relevant part, the CBA governs the employee Performance Management process, the award of spot bonuses (“lump sum cash payments”) and other financial and nonfinancial awards to employees, annual and sick leave, and overtime and premium pay.

The CFPB also enters into separate Compensation Agreements with the union, which govern the award of employee raises, bonuses, and benefits, and typically have a duration of two to three years. The CFPB does not make these Compensation Agreements available to the public on its website (the information below derives from another source). Notably, the CFPB’s Inspector General identified achieving the perceived transparency of the CFPB’s compensation system as a major management challenge for the CFPB in 2023. The CFPB and the union executed the current Compensation Agreement on December 17, 2020. The Compensation Agreement governs bargaining unit employee compensation for calendar years 2021, 2022, and 2023. The CFPB and the union are presently negotiating a new agreement to replace this agreement when it expires on December 31, 2023. The Compensation Agreement currently in effect provides as follows:

- Employees receive an automatic 3% raise each year in 2021, 2022, and 2023;

- [Note: To be eligible to receive raises, employees must receive an “accomplished performer” annual performance rating. However, the CFPB abandoned its 5-tier performance management rating system in 2014. As a result, under the current CBA, annual employee performance is measured only on a pass/fail basis, with virtually all employees receiving an “accomplished performer” performance rating each year. Consequently, virtually all bargaining unit employees are automatically eligible for raises each year. The same goes for eligibility for lump sum bonuses referenced below.]

- Employees also receive an automatic 3% lump sum bonus each year in 2021, 2022, and 2023;

- Employees working in certain geographic areas at certain pay grades will also receive locality pay increases to their base salaries;

- Minimum and maximum pay band amounts were increased by 1% in 2021;

- Guaranteed employee benefits include:

- Retirement (Fed pension plan; 100% CFPB paid; vested after five years);

- Thrift Savings Plan;

- Federal Reserve System Thrift Plan (CFPB matches at 7% in addition to 1% automatic agency contribution);

- Federal Employees Health Benefits (FEHB) (CFPB pays 72% on average plus additional $75 premium subsidy per pay period);

- Domestic Partner Health Insurance Subsidy;

- CFPB Dental and Vision Plan (100% CFPB-paid premium);

- Federal Employees Dental and Vision Insurance Program (FED VIP);

- Flexible Spending Account (FSA) (some employees eligible for $500 paid by CFPB annually);

- CFPB and FEGLI Life Insurance Programs;

- Death in Service Benefits (100% CFPB-paid Basic coverage);

- Long Term Disability (100% CFPB-paid);

- Short Term Disability (100% CFPB-paid);

- Federal Long Term Care Insurance Program (100% CFPB-paid);

- 24-Hour Personal Accident Insurance;

- Business Travel Accident Insurance (100% CFPB-paid);

- Physical Exam Program (tax-free reimbursement of expenses);

- Work/Life services including Employee Assistance Program and emergency back-up dependent care;

- $1,000 cash “signing bonus” for eligible new employees;

- Academic Assistance Program of $3,000 per year for eligible employees;

- 12 weeks (480 hours) of Paid Parental Leave; and

- A new Special Bonus Program (to be determined later).

The number of CFPB full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) increased significantly over time, particularly during its start-up growth period between FY 10 and FY 13 (see Figure 6). But even after this period, between FY 13 and FY 22, the CFPB added a net 297 FTEs. By comparison, the FTC, which is subject to Congressional appropriations, reduced staff by a net 25 FTEs over the same period.

Average compensation per CFPB employee has also increased over time. For example, average compensation (salary and benefits) per CFPB employee increased from $138,351 in FY 2012 to $231,556 in FY 2022, for a CAGR of 5.3%. By comparison, according to FTC data, the average compensation per FTC employee increased at a CAGR of just 1.29% between FY 12 and FY 22. Similarly, data from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), which is funded primarily by bank assessments, shows that the average compensation per OCC employee increased at a CAGR of just 1.61% during the same period. The average CFPB salary in FY 2021 ($155,374) was about 275 percent greater than the median earnings for a full-time, year-around worker in the U.S. in FY 2021, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates.

Over time, CFPB employee benefits have also increased in proportion to overall compensation. In FY 12, benefits comprised 25% of total compensation (equivalent to 33% of salary), whereas in FY 22 benefits comprised 30% of total compensation (equivalent to over 43% of salary). Between FY 12 and FY 22, average benefits per employee grew at a CAGR of 6.7%, while average salary per employee grew at a CAGR of 4.75%.

On December 7, 2022, the CFPB and the employee union entered into a “Compensation Reform Pay Reset” agreement. According to the CFPB, the goal of the agreement includes “fostering internal pay equity.” The agreement requires CFPB to adopt a new formula for calculating creditable service and using the resulting scores to reset base salaries for CFPB employes. The agreement also requires base salary range minimums and maximums for all pay bands to be readjusted in 2023. According to the CFPB labor union, these changes will result in additional salary increases for bargaining unit employees in 2023 that exceed $17,000 on average.

B.) Contracts and Support Services

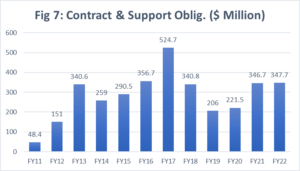

The CFPB has incurred $3.4 billion in obligations for Contract & Support Services between FY 11 and FY 22, amounting to approximately 51% of all obligations incurred by the CFPB for this period. See Figure 7 for the CFPB’s annual fiscal year obligations for Contract & Support Services.

These obligations include two main components: (1) interagency agreements (IAA) with other Federal agencies and other Federal payments made to Federal agencies, and (2) contracts with private sector entities.

IAA obligations are typically not reported in USASpending.gov. It is not known how much CFPB obligated for IAAs in FY 11 and FY 12, but between FY 13 and FY 22, the aggregate amount of such obligations was $973.3 million (or about 30% of total obligations for contract and support services during this period). These awards include rents paid to the Office of Comptroller of the Currency pursuant to a long-term occupancy agreement to rent its headquarters building at 1700 G Street NW, an initial award ($145.1 million) to the General Services Administration to renovate the 1700 G Street NW building, and cumulative annual payments totaling $123.4 million to the Fed Board of Governors to fund the Office of the Inspector General, which the CFPB shares with the Fed.

Regarding contracts with private sector entities, Section 743 of Division C of the Fiscal Year (FY) 2010 Consolidated Appropriations Act, P.L. 111-117, requires civilian agencies to prepare an annual inventory of their service contracts that exceed $25,000 in value. For each service contract listed in the inventory, the law requires the agency to include a description of the services purchased, the total dollar amount obligated and invoiced for services under the contract, and the contract type and date of award. Federal Acquisition Regulation Subpart 4.17, which implements the law, further requires agencies to submit the inventory to the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) by January 15 annually. Then, each agency must post the inventory on its website and publish a Federal Register Notice of Availability by February 15 annually. For unknown reasons, the CFPB has not posted the required service contract inventories and analyses for FY 20 or FY 21 to its website. Additionally, a search of the Federal Register appears to reflect that the CFPB did not publish the required notices of availability for its FY 12, FY 15, FY 17, FY 20, or FY21 inventories.

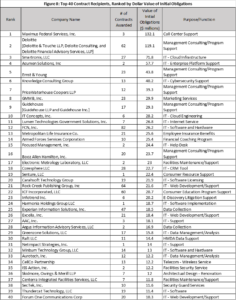

Despite these limitations, some information is available regarding CFPB contracting with private sector entities. For example, a search of the USASpending.gov database contains 3,874 contracts funded by the CFPB since FY 11, with a total obligated value of $1.78 billion. Using this data, the top forty individual awardees (ranked by aggregate dollar value of obligated amounts across all contracts awarded) appear in Figure 8 below.

Other aspects of CFPB contracting within the database are not as transparent, however. For example, the CFPB has obligated approximately $41.6 million for expert witness services, but the identities of the individuals used by the CFPB as expert witnesses in litigation or for other purposes are usually not disclosed.

IV. The Effect of the CFPB Funding Mechanism on Legislation

Because the CFPB is not subject to regular Congressional appropriations, its expenditures are scored as direct rather than discretionary spending for federal budgetary purposes. This means that any legislation requiring the CFPB to undertake a particular action will “score” as an increase in direct spending compared to the baseline, which implicates statutory “pay-as-you-go” requirements, as well as applicable House and Senate PAYGO or CUTGO rules. In practice, this means that any legislation affecting the CFPB requires a “pay-for” to reduce direct spending to offset the projected cost.

As an example, in 2014, the House Committee on Financial Services considered H.R. 4662, a bill that would have required the CFPB to establish a procedure for publicly issuing advisory opinions to resolve regulatory uncertainty in the financial services marketplace. In producing a cost estimate for the bill, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) was required to rely on information provided to it by the CFPB. The CFPB estimated that it would receive 5,000 requests for advisory opinions per year in perpetuity (or 50,000 requests within the 10-year budget window), and that each response would require 10-30 days of staff time. Using these figures, the CBO issued a cost estimate concluding that the bill would increase direct spending by $815 million within the 10-year budget window. Such a score required a direct spending offset, and the difficulty in identifying such an offset within the Committee’s jurisdiction derailed consideration of the bill on the House floor. Notably, the CFPB announced an advisory opinion program on its own initiative on November 30, 2020; since that date, the CFPB has issued a total of ten advisory opinions.

V. Conclusion

We hope this primer helps explain how the CFPB obtains and expends its funding and the effect of its statutory funding mechanism on federal budgeting and legislation. Please reach out with any questions.